Anyone who does a simple literature search will encounter

a plethora of articles discussing, debating, and even arguing over this topic.

The reasons for all of these issues, in our opinion, has to do with numerous

inconsistencies among studies in the doses and duration of ibuprofen used, the

timing of ibuprofen dosing in relation to the administration of aspirin, the

dose and formulation (enteric or non-enteric coated) of aspirin used, the

patient population studied (healthy volunteers vs. patients with known

cardiovascular disease (CVD)), whether surrogate laboratory markers were used

versus tests that actually assess platelet aggregation, and lastly the study

design used by the investigators to generate their findings.1-6 As such,

it is very difficult, to nearly impossible, to extrapolate the current data

from each of these studies, all of which have limitations or inconsistencies

among each other, and generate a definitive answer that can actually translate

into clinically meaningful endpoints that are applicable to the general

population. Some of the discrepancies in the literature may be due to the

ability of platelets to aggregate at times when the concentrations of the

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are low versus early on after

administration when concentrations are higher.7 By the time the ibuprofen

is freed from the binding site in COX-1, some of the aspirin will already have

been eliminated from the body.

The

Food & Drug Administration (FDA) warning to healthcare professionals

recently stated, "Patients who use immediate release aspirin (not enteric

coated) and take a single dose of ibuprofen 400 mg should dose the ibuprofen at

least 30 minutes or longer after aspirin ingestion, or more than 8 hours before

aspirin ingestion to avoid attenuation of aspirin's effect. In addition,

there are a number of studies with conflicting findings."8 Based on

this recommendation, the purpose of this issue is not to critique every single

study published on this subject, but rather to explain the proposed mechanism

for the drug interaction and then to highlight some of the issues with its

interpretation in relation to the medical literature.

What

happens during normal platelet aggregation?

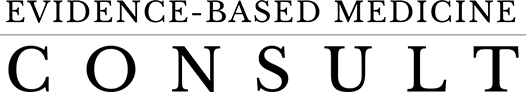

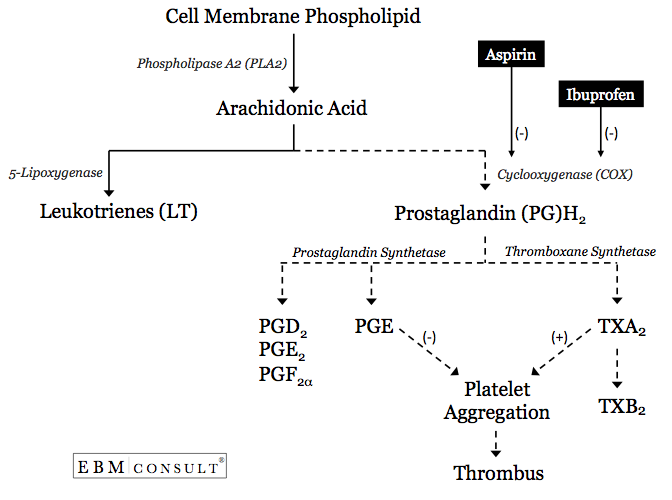

- The process of increased platelet aggregation begins with

the release of arachidonic acid (AA) from the cell membrane of a

platelet.6

- The AA can then goes down one of two metabolic pathways, the

lipoxygenase pathway, which will generate leukotrienes (LT), or the

cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 pathway to form prostaglandin (PG) H2.9 Prostaglandin H2 can then be metabolized by prostaglandin

synthetase to form other PGs or it can be metabolized by thromboxane (TX)

synthetase to form TXA2.

- If TXA2 is formed then platelet aggregation will

be facilitated or encouraged.10 This specifically occurs when AA is able

to travel through a hydrophobic channel where it can make contact with

catalytic site within the COX-1 enzyme. If this channel or the area

surrounding the catalytic site is blocked, the AA will be unable to be

metabolized to PGH2 and then onto TXA2, thereby reducing the likelihood for

platelet aggregation.6,9,11

How

does aspirin then interfere with platelet aggregation?

- Upon administration of aspirin, it will irreversibly

acetylate a serine residue at position 529 within the hydrophobic channel,

which is in close proximity to the catalytic site where AA can be metabolize to

platelet derived TXA2 by COX-1 enzyme.6,9,11 The acetylation of this area

creates a blockade where AA will not be able to gain access to the catalytic

site within COX-1.

- Since aspirin does this irreversibly, the ability of

that catalytic site within COX-1 enzyme to metabolize AA is blocked or

inhibited for the life of that platelet (usually around 7-12 days). This

is one of the main reasons aspirin confers a cardioprotective benefit against

cardiovascular events when primarily being used for secondary prevention.

- Therefore, if anything else competes or blocks aspirin's access to acetylate

this serine residue within the COX-1 enzyme, the cardioprotective benefits may

be diminished.

How

does ibuprofen interfere with the pharmacologic activity of aspirin?

- As with all of the NSAIDs, ibuprofen is a reversible,

competitive inhibitor of the catalytic site for AA metabolism within the

hydrophobic channel of the COX-1 enzyme.7,12

- The presence of ibuprofen

within this hydrophobic channel competitively blocks the access of aspirin to

acetylate the serine residue that is in close proximity to the catalytic site

for AA.7,12,13

- The degree of inhibition of aspirin's access to exert its

pharmacologic effect by ibuprofen is going to be influenced by a number of

factors.

The

first and most obvious factor has to do with the order with which aspirin and

ibuprofen are administered in relation to each other. If the aspirin is

given first, it will gain access to irreversibly acetylate the serine residue

within the COX-1 enzyme. Remember, once aspirin has irreversibly

inhibited the COX-1 enzyme, the antiplatelet effect will continue to exist for

the life for that platelet. The next factor is the concentration of

ibuprofen present in relation to the time of co-administration of

aspirin. Since ibuprofen's inhibition is competitive, platelet

aggregation is not only influenced by the concentration of ibuprofen present,

but is also reversible in nature. Therefore, as the drug levels decrease

through elimination pathways, the amount of ibuprofen able to block aspirin's

access to its active site also decreases, especially given its short half-life

of 2-4 hours.14 This pharmacokinetic characteristic of ibuprofen is the

reason why it must re-dosed multiple times throughout the day, whereas aspirin

is only dosed once a day. Therefore, one can see why there is variation

in the findings from multiple studies published in the medical

literature. Thus the clinical impact of this drug interaction is

influenced by the order in which the two medications are administered, the dose

and formulation of aspirin used, the dose and frequency of administration of

ibuprofen used, the patient population studied, and the type of endpoint from

that study.

In

the end, the real question is whether this interaction translates into a clinically

relevant pre-defined patient oriented cardiovascular defined outcome. To

our knowledge no such prospective, appropriately designed clinical trial has

been done to answer this question with convincing data in the population of

patients in question.

References:

- Gengo

FM, Rubin L, Robson M et al. Effects of ibuprofen on the magnitude and

duration of aspirin's inhibition of platelet aggregation: clinical consequences

in stroke prophylaxis. J Clin Pharmacol 2008;48:117-22.

- Gladding

PA, Webster MWI, Farrell HB et al. The antiplatelet effect of six

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and their pharmacodynamic interactions

with aspirin in healthy volunteers. Am J Cardiol

2008;101:1060-1063.

- Cryer

B, Berlin RG, Copper SA et al. Double-blind, randomized, parallel,

placebo-controlled study of ibuprofen effects on thromboxane B2 concentrations

in aspirin-treated healthy adult volunteers. Clin Ther

2005;27:185-191.

- MacDonald

TM, Wei L et al. Effect of ibuprofen on cardioprotective effect of

aspirin. Lancet 2003;361:573-74.

- Kurth

T, Glynn RJ, Walker AM et al. Inhibition of clinical benefits of aspirin

on first myocardial infarction by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Circulation 2003;108:1191-1195.

- Catella-Lawson

F, Reilly MP, Kapoor SC et al. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors and the

antiplatelet effects of aspirin. N Engl J Med

2001;345:1809-17.

- Evans

AM. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the profens:

enantioselectivity, clinical implications, and special reference to

S(+)-ibuprofen. J Clin Pharmacol 1996;36:7S-15S.

- Food

& Drug Administration. Information for healthcare professionals:

concomitant use of ibuprofen and aspirin. U.S. Department of Health &

Human Services. Last accessed: 09-19-2011.

- Funk

CD, Funk LB, Kennedy ME et al. Human platelet/erythroleukemia cell

prostaglandin G/H synthase: cDNA cloning, expression, and gene chromosomal

assignment. FASEB J 1991;5:2304-12.

- Fitzgerald

GA. Mechanisms of platelet activation: thromboxane A2 as an amplifying

signal for other agonists. Am J Cardiol 1991;68:11B-15B.

- Loll

PJ, Picot D, Garavito RM. The structural basis of aspirin activity

inferred from the crystal structure of inactivated prostaglandin H2

synthase. Nat Struct Biol 1995;2:637-43.

- Loll

PJ, Picot D, Ekabo O et al. Synthesis and use of iodinated nonsteroidal

antiinflammatory drug analogs as crystallographic probes of the prostaglandin

H2 synthase cyclooxygenase active site. Biochemistry

1996;35:7330-40.

- Rao

GH, Johnson GG, Reddy KR et al. Ibuprofen protects platelet

cyclooxygenase from irreversible inhibition by aspirin.

Arteriosclerosis 1983;3:383-8.